Your Cart is Empty

FREE SHIPPING FOR ALL ORDERS $200+

Menu

-

- Shop

- Shop by Brand

- Custom Mattresses

- Why Wholesome Linen?

- Learn & Inspire

- Sleep Safety Lab

- The Journal

- Eco Eve's Weekly Pregnancy Guide Podcast - Natural & Holistic Guide by Wholesome Linen

- Natural Baby Nursery Guide 2025 - Pure, Non-Toxic Essentials

- The Science Behind Flax Linen Weighted Blankets: Benefits for Sleep, Anxiety, and More

- The Evolution of Baby Cradles: From Vintage Wood to Modern Marvels

- When Can a Toddler Have a Pillow? - The Ultimate Guide to Eco-Friendly and Natural Options

- Gifting

-

- +1.213.444.6072

- Login

FREE SHIPPING FOR ALL ORDERS $200+

8 Step Process Of Turning Flax Plant Into Natural Linen Fiber

April 30, 2016 3 min read

Flax has been with humankind long before Europeans' discovery of the Western Hemisphere. Linum angostifolium, the wild ancestor of flax, can be found from the Black Sea to the Canary Islands. Linus usitatissimum (meaning "of greatest use"), is the oldest cultivated fiber plant, with evidence of its growth and use dating back to the fifth millennium BC in both Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Linum angostifolium- the wild ancestor of modern flax

Linususitatissimum is believed by many historians to have been introduced into England by the Romans; by the 16th century, laws were enacted requiring that a quarter of an acre (one rood) of flax be planted for every sixty acres under cultivation.

Arquivo Municipal Alfredo Pimenta Museum, Guamaraes, Portugal

Flax has many advantages as a fiber crop, its overwhelming disadvantage is the amount of labor, skilled and otherwise, required from sowing to harvest.

Here is great educational video from England in the 1940's explaining the process of turning flax into a fiber.

1. PLANTING FLAX

Flax needs a deep, rich soil, and, like tobacco, quickly depletes the nutrients from the land where it is planted. In early settlement days in Virginia, that meant it could only be raised on newly-cleared ground. After two or three years of a flax crop, a farmer needed to sow a less nutritionally-demanding crop, such as wheat.

2. GROWING FLAX

Later in the colonial period, farmers could incorporate flax into a rotation process which included heavy dunging or the sowing of cow peas a year or two before the next flax crop was to be planted. After plowing in November, February and March, the ground was harrowed and raked fine. The small, oily flaxseeds were sown broadcast in April and a final harrowing took place. The closer the seeds were spaced, the less branching took place in the resultant plants and the higher the quality of the crop. If flax is sown properly, weeding is unnecessary because there is no space for unwanted plants.

3. HARVESTING FLAX

Flax takes about a hundred days to mature. When the leaves yellow and the seed turn brown, the flax is pulled from the ground by the roots, spread to dry for a few days, and, if time was not a factor, stored until the next year to age. Processing flax is an extremely labor-intensive process, providing skilled and unskilled employment for both adults and children.

4. RIPPLING FLAX

First, the upper part of the flax bundles are drawn through coarse combs to remove seed in a process called rippling. After the seeds are removed, it is necessary to separate the long, silky inner fibers which constitute the end product from the straw and inner pitch.

5. RETTING FLAX

Retting, in which the unwanted fibers are loosened and decomposed, can be achieved in several ways. The flax can be left out in the field, where the exposure to the elements, particularly the moisture in the air, can do the work. A pond or through can be used to achieve the same effect in much less time, but with a prodigious odor. The ideal way to ret flax is to expose it to constantly running water, such as a stream. The amount to time this step requires depends on the quality of the flax, the temperature and numerous other variables.

6. DRYING FLAX

When the straw comes away easily from the few bent fibers, it is time to grass the flax. The bundles are untied and laid in a field for a few days until they are dried on one side, then turned so the other side can be dried. When the crop is thoroughly moisture free, it is stacked inside to age for a few more weeks.

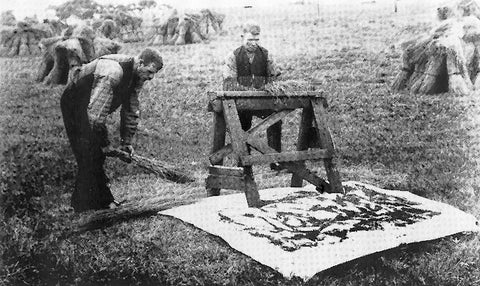

7. SCUTCHING FLAX

Next, a series of steps free the linen fiber from the boon (unwanted plant material). The brake, a large wooden machine, is used to break down the trash material and loosen it further from the end product. Then the flax is scutched (beaten against a board with a blunt wooden knife).

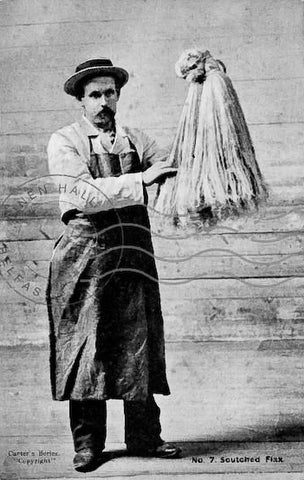

8. HACKLING FLAX

The final process is hackling, in which the fiber is drawn through a series of metal combs to remove the last of the boon and shorter fibers. The end result is a strick, a half-pound bundle of long, light grey fibers which resemble human hair.

We hope you learned something new & wholesome today. Check out our line of woven flax linen baby and toddler sleep essentials. We use only organic non bleached linen fabrics and raw flax fibers made with the same process listed above.

#LETSMAKEITWHOLESOME

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …